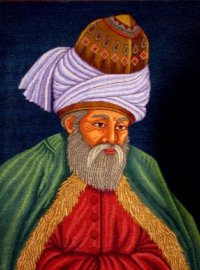

Reading Rumi

Rumi is a poet of love, but he started life as a scholar. When he was thirty seven he met his master, the mysterious Shams of Tabriz. They had an ecstatic friendship that lasted for only three years and that profoundly changed Rumi’s life. From scholar he became mystic. When, after three years, Shams disappeared, Rumi consoled himself with poetry, writing about his lost love, writing about merging with the absolute in the manner he had merged with Shams.

There is something mysterious and dangerous about merging. When we completely merge with another human being we lose our sense of individuality. This state of merging is blissful but never permanent, and when we find ourselves again, desillusion or a strong negative emotional reaction may set in. Romantic love affairs can be like this. As long as we are completely in love we cannot find fault anywhere in the blissful state that we have created together, and when we fall out of that state it may look like it was all just an illusion.

For Rumi it was completely different. For Rumi the state of love he had experienced with Shams was a foreshadowing for the state of absolute love that he discovered in himself. He became a singer and dancer and story teller who used prose and verse to express and celebrate his ecstatic love affair with the universe. He had become drunk, forever, with absolute love. And he invites us to partake in the joy.

When I write poetry, I do not know what is going to come. Once the first lines appear I reflect and rearrange, but the process itself is utterly mysterious to me, and the beauty is in the mystery. Because of this experience you can imagine my delight in reading the following lines by Rumi:

Who says words with my mouth?

Who looks out with my eyes? What is

the soul? I cannot stop asking.

If I could taste one sip of an answer,

I could break out of this prison for drunks.

I didn’t come here of my own accord,

and I can’t leave that way.

Whoever brought me here will have to take me home.

This poetry. I never know what I’m going to say.

I don’t plan it.

When I’m outside the saying of it,

I get very quiet and rarely speak at all.

I know this experience very well, of being outside the saying of the words that mysteriously appear when I am writing. It happens when I dwell in the empty space where words do not yet exist but can blossom into existence. Rumi’s poem gives a description of what it means to dwell in that space. This is also a description of self inquiry, the process of putting one’s attention on awareness itself, and then sinking into it, and finding that there is nothing left to say, that there is a silence there that no words can improve upon. And then, just like Rumi, I can get very quiet.