Groupthink

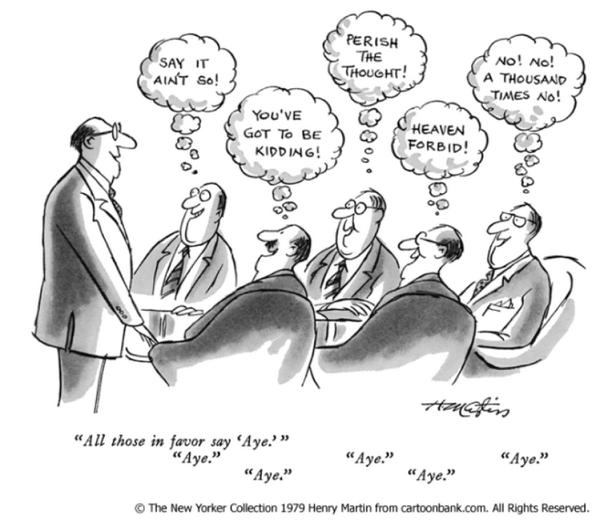

Before reading this post, please first watch this video. The context in which groupthink is discussed is usually opinion formation for decision making. The key questions in a group decision making setting are always: Do the group members feel free to form their own judgement? Do they feel free to rely on their own judgement? Do they feel free to articulate their own judgement? Groupthink occurs when group loyalty interferes with independent thinking, when people’s desire to maintain group loyalty becomes more important than making up their own minds or arriving at the best choices.

If you have watched the video then you will have grasped the message that groupthink is bad because it leads us astray. But there is another side to this. We are all dependent on those around us for our very survival. And our thinking uses language, essentially a group phenomenon. We all need others to learn about ourselves, to hone our opinions, to explore our feelings. We all have to negotiate all the time between our urge to be articulate and independent and our need to accommodate and belong.

Logicians and social scientists have studied a phenomenon called an information cascade. Here is a laboratory example. Imagine two urns A and B, both filled with marbles, either black or white. It is commonly known that urn A contains twice as many black marbles as white marbles, while urn B contains twice as many white marbles as black marbles. It is also common knowledge that one (and only one) of these two urns is placed in a room, where people are allowed to enter one by one. Each person draws randomly one marble from the urn in the room, looks at it and puts it back. The person then makes a guess as to whether the urn is the room is urn A or urn B. These guesses are recorded on a slate in the room, so that the next person can see the list of previous guesses. Now imagine what will happen …

The point of the example is that recorded information about the experience of others can lead us astray. For assume that urn A is in the room, and you enter, and you happen to draw a white marble from it. Since you have no other information than that, it is reasonable for you to guess you are drawing from B, the urn with 2/3 white marbles. Next I enter, and I draw a black marble. I also see that your guess was B, and I conclude that the marble you drew was white. So one black and one white marble were drawn. Hmm. That makes A and B equally likely. So I toss a coin to make up my mind, and I record B. Now the third person enters. She draws black, but she sees BB. She weighs this against her own evidence, and … records B. And so on. Nobody is behaving irrationally, and still they all draw the wrong conclusion.

Suppose the participants would have been allowed to record their evidence rather than their judgement. In that case the accumulating information would have helped to make their guesses ever more informed. This points one way out of groupthink: sometimes it can simply be avoided if the group members each decide to rely more on their own direct evidence. Drop your stories and rely on what you experience instead, is often sound advice.

But sometimes this is difficult. In Andersen’s fairy tale about the emperor’s new clothes, why do the emperor’s ministers pretend to see what is not there? Because the clothes were sold to the emperor by two swindlers who pretended that the clothes were invisible to anyone who was unfit for his position or otherwise hopelessly stupid. The emperor is fooled. The ministers are dependent on the emperor, and understandably reluctant to embarrass their master. The child who blurts out The emperor is not wearing any clothes is too young and innocent to understand the desirability of not appearing unfit or stupid, and does not understand the first thing about the power of the souvereign and the need not to expose him as a fool.

Why did this tale become so popular? Because naked emperor situations abound in real life. Examples are all cases where people act against their own evidence and judgement because the power they perceive to have derives from the group. We see this every week in the press briefings of the Trump adminstration. Michael Wolffs Fire and Fury makes very clear that everyone in the direct circle around Trump knows that their boss does have a limited attention span. They all have seen with their own eyes that Trump gets bored and irritable if staff members try to provide him with relevant facts and serious information. They all know that Trump believes whatever he chooses to believe. They play along only because they believe it is to their advantage. As Michael Wolff puts it, they have become expert at method acting to stay in tune with their boss.

In my boarding school days, there was the implicit assumption that the worldview of the Roman Catholic Church was superior to everything that other parts of our gymnasium curriculum taught us about Greek and Roman culture. No doubt, these cultures also considered themselves superior to the cultures around them. The Greeks believed that other people spoke in inarticulate grunts of bar, bar, and they called them barbaroi. They felt different from them and elevated above them. Just like we, members of the True Apostolic Church, felt different and elevated, for we considered our creed superior to other creeds. But why were the non-members wrong and were we right? When I tried to discuss these matters with the friars who were my teachers they somehow suggested that I was too smart for my own good.

Later on, as a student of philosophy, I found myself surrounded by fellow students with political views that were at the far left on the spectrum. There was a widespread belief among students in the 1970s that philosophy was about social change, and that one’s time at the university was a preparation for the real work at hand: molding a better society. I was a middle-of-the-road social democrat myself, and an advocate of openness, tolerance and moderation. I studied Poppers’ Open Society and Its Enemies and read Solzhenitsyn’s work, and I could not understand for the life of me why anyone who had read Solzhenitsyn could still believe in social revolution. But the point is, to read and appreciate Karl Popper and Alexandr Solzhenitsyn and Arthur Koestler and George Orwell and Leszek Kolakowski you have to already be in possession of a somewhat open mind.

Discussions with fellow students about world views could become very uncomfortable, even acrimonious, in those days. Often, it did not feel at all like free exchange of ideas. Maybe it could not be, for we were all struggling with finding our own identities, shaping our world views, and the process was often painful. As a joke, I once wrote a spoof article in the heavy jargon of hermeneutic thinking, signed it with a fake name, and got it published in the local bulletin of our philosophy department. To my surprise the paper was taken very seriously and it drew several replies in the same style. So it was just a game! Later, some of the people who found out that they had been fooled were seriously mad at me.

I got disillusioned with philosophical quibbles altogether and I decided to switch to the only areas of philosophy where I could believe in progress: logic and analysis. But even this field is not without groupthink. In analytic philosophy it is customary to declare certain topics off limits. Metaphysics, speculations about the ultimate nature of reality, are a case in point. “Whereof one cannot speak, thereof must one be silent,” to quote Ludwig Wittgenstein. This may sound deep, but it is very unhelpful. We all want to lead a meaningful life, so we have to search for meaning with all the means available to us. Explanations that the quest is impossible either make us miserable or they are an invitation to cultivate an attitude of ironic distance to life, the kind of worldly wisdom that mocks those who take life as anything but an ultimately meaningless silly game. I have a naturally cheerful disposition, so the misery has no appeal, and a life of irony does also not work for me.

Now I have turned into an existentialist philosopher, and I engage with fun people who are in for running experiments with life. And I have realized something that my philosophy teachers have failed to tell me: my intellect is not my only tool, far from it. So I looked for guidance in meditation, and I started a practice. I practiced martial art. I got serious about yoga. I tried to engage with people at a more authentic level, and for that I trained in improvisation theatre with Helmert Woudenberg. I visited Thich Nhat Hanh, I attended many of his dharma talks, and I was deeply impressed by him. I still am, and I now know the difference between a real dharma talk and an imitation. I got interested in massage, and I am now training as a Shiatsu practitioner. I experienced that all these practices changed my outlook on life more radically than reading books. And I encountered more groupthink in all the places that I visited.

In the 1990s in Amsterdam I took part in events and training organized by the Fun Theatre Group. The founders of this group had a background in theatre, and they offered courses in improvised play. But they also gave – or pretended to give – guidance in personal growth. They threw great parties that attracted fun people, and they organized weekends of juicy entertainment and exploration. There also was a less bright side: people who were sucked into the inner circle of this and became dependent on the group to get their bearings in life. This had to lead to serious disappointment, especially in view of the fact that some of the core beliefs of the group were plain silly. Of course, the silliness could only be seen from a certain distance. So I took great care to maintain that distance. I could see people struggle to escape from the value system of the group. They struggled because they somehow seemed to believe the group judgement of what they were worth. They had swallowed the conviction that it would be disastrous for them to distance themselves. Later on, Dutch playwright and actor Helmert Woudenberg created a play about this, Wij zijn God (We are God). If you read Dutch, you might wish to check this link.

So I have been around, and I have collected some experience. I see patterns that I have seen before. A thing that worries me is that the Circling and Authentic Relating community that I love and that I feel I belong to is not all that different from the Fun Theatre group. There are lots of common denominators: interest in authentic communication skills, bio-energetics, Jungean archetypes, tantra, playing with masculine-feminine polarity, spiritual growth. Some of it very beautiful, all of it at least quite intriguing.

There are differences too. Sai Baba and Bhagwan have been replaced by Ken Wilber, but to me it is doubtful whether this is a real improvement. I am aware that this is a judgement, and I confess that the glib quasi-academic prose style of Wilber – another bunch of judgements – annoys me. Who would I be without all these judgements? No doubt there is a precious lesson somewhere hidden under my ire. No irony intended. For now, let’s just say that Wilber is not for me, probably never will be, and leave it at that. Just a matter of taste.

My intellect is an important tool, and I cherish my ability to distinguish and judge. We all have to choose, moment by moment, which influences to admit in our lives and which to avoid. Our sense of discrimination combines the qualities of head and heart. Mind you, the distinctions that our intellect provides are not once and forever. They can dissolve again in heart-felt reflection, to wipe the slate clean for deeper and deeper understanding. And this process goes on forever.

A key difference between Fun Theatre and circling, for me, is the emphasis in circling on self-understanding, (self-)empathy and honest self-expression. I am grateful I have discovered this express line to heart-to-heart communication, and I deeply appreciate the rapid shifts that it provides in what we can experience together in the moment. Circling events, to me, are truly wonderful invitations to engage in nonviolent communication in energetic and dynamic ways.

And there are group processes going on that are similar to what I encountered with Fun Theatre. Again, the leaders of the group are convinced that they are pioneers playing a role in changing world consciousness. Again the inner group has a clear hierarchy created and maintained by groupthink. Fun Theatre classified people as white, red, black, grey character types, with the greys at the bottom, and if I remember correctly, I was once classified as grey. Circling Europe has a hierarchy of skill levels in facilitation, with people worrying about their assessment, or complaining at the end of a training course that they deserve a higher level than the course leaders are willing to stamp on them. Again the groupthink has a pitfall, for by buying into the hierarchy we run a serious risk of giving our power and autonomy away.

It is sweet to belong, and it is painful to take the distance that is necessary to observe what goes on and write these comments. It feels risky to come from a place that can be perceived as the spot of the critical outsider who does harm to the community. I am saying the things that I am afraid this community does not want to hear, and I am aware of it. Why do I do this? I am not quite as naive as the boy who exposes the emperor. I still want to belong. I write these sentences with trepidation. No malice is intended, there is no unprovoked desire to do harm or produce evil, as far as I can see now.

The circling and authentic relating community is a great community, and the core of the practice that we are trying to develop together is beautiful and deep. When I encounter you, you can be of great help to me. You can help me to discover things about myself that I would have great difficulty to discover on my own. And I can do the same for you, should you wish to engage with me. But, each of us, we have to remain true to our own selves. We must discover in ourselves and for ourselves who we truly are, and it follows, as the night the day, in which areas we have to grow and in which direction we have to go. And in this way, I cannot be false to any one of you.