Why Are Intellectuals Not Looking At the Whole Picture?

Jan van Eijck

Edited on March 9

The title question was raised on Facebook by professor Rohit Parikh, a distinguished colleague who is concerned about the present state of intellectual public debate, in the US and globally on internet. Rather than commenting on it on Facebook, let me offer some reflections here.

The whole picture, in one fell swoop, without detail, is that we now see the rise of populism in the United States. Populism is now so clearly visible that it can no longer be denied, not even by academics who are used to living in a privileged universe of their own. Intellectuals are getting scared because, with few exceptions, they had not seen it coming. We have not seen it coming because we have not bothered to look. Some of us may have felt uneasy, but we managed to tell ourselves that it did not matter, that it did not concern us, that it would not affect us. We have not seen it coming because we were, most of us, lost in the Glassperlenspiel, the glass bead game, of our chosen professions, and in artificial quibbles of no substance that only have reality within our privileged social bubbles.

How could this have happened? Why did so few members of academia see what was unfolding itself? Specialisation myopia apart, this is mainly because of preoccupation with elitist issues, and obsession with correct speech. Unisex public toilets do not offend me, but I cannot understand why they are in any sense important. We have unisex private toilets at home, so who cares? Declaring this a key issue in the struggle to improve the human condition is, well, strange. It shows you are alienated from reality.

Worries about correct speech, about anti-discrimination protections for the workforce (regarding race, color, religion, national origin, sex, pregnancy status, age, disability, what have you) are mainly about words, and almost never about reality. They are about how we are allowed to talk about things, and almost never about how things are. Words are soothing. They have the power to shield us from the harsh realities of a money-dominated world of inequality and inhumanity, in the US, and also in Europe. Well, maybe still a bit less, in Europe.

“Expecting Mothers” offends transgenders, so doctors in Britain have been instructed, in 2016, to refer to mothers as “pregnant people”. These are the new guidelines from the British Medical Association. Google for BMA-guide-to-effective-communication-2016.pdf if you wish to convince yourself that I am not joking. What you can see in this booklet is the confusion between the fight against stereotypes on one hand and seeing the world as it really is and being allowed to call a spade a spade, on the other. Calling things by their true names is an important practice for keeping us sane. Men and women are different, and it is the women that get pregnant, not the men. One should be allowed to say so. No offence meant.

I am a white male. I had the good luck that I was born and raised in a civilized country, the Netherlands. I have a certain age. I have had privileges of education, for sure. These facts and labels are true of me in a certain sense, but they do not determine me. I am aware that I should wear them lightly, and I am aware that the same holds for similar labels that I apply to fellow human beings that I encounter. Labels, most labels, when applied to me, do not offend me. Sometimes I have to use similar labels to communicate with or communicate about those around me. All words are labels. If I use words, labels, with respect, as aids in seeing things as they are, in communicating about the world as I see it, shouldn’t that be all right? No offence meant.

For the record, I am all in favour of transgender rights. What they did to Chelsea Manning was an outrage, but orthogonal to the fact that she is transgender. Being forbidden to sit in the front of a bus because of your skin color was an outrage, and I admire Rosa Parks for what she dared to do. But non-unisex toilets are of a different order, and separate sex toilets are certainly not an outrage.

Obama’s administration issued a directive allowing transgender people at schools to use bathrooms matching their gender identity, and this has clashed with the state laws of certain conservative states like North Carolina. These state laws insist that pupils use school bathrooms of their birth gender. One side maintains that every student (including transgenders) should be treated fairly and supported by teachers and schools, while the other side protests against an executive order forcing transgender policies on schools and on parents who clearly do not want it. The bare fact that this got so out of hand seems to suggest that Obama’s attempt at nationwide regulation was not a wise move, because large parts of the country were simply not ready for it. Why force this down the throats of people who do not want to swallow it?

So why don’t we talk about things that are a lot more pressing, instead? Here is one such thing, a huge thing: the horrors of a privatized prison system in the US that literally enslaves a substantial part of the population, many more blacks than whites. This is huge. In 2014, 6 percent of all black males in the US aged 30 to 39 were in prison. Six in one hundred, this is an almost incredible percentage. So if someone can convince me that it is not true, then please tell me, for it would make me sleep better. But the figure is from the US Bureau of Justice, and I got it from Wikipedia.

This system is partly kept in place by a class of slave holders that have financial interests in keeping it in place, for many US prisons are run for profit. There are words for it: the private prison industry, the prison-industrial complex. Here are some more words, some more labels: this is modern slavery, literal slavery. If you want to know, and if you are a US intellectual you should want to know, then please read the Wikipedia article on incarceration in the United States. If you want to know what it feels like to be a prisoner in this system, read the story of Anthony Papa. If you want to know what it is like to be a prison guard in the US, read Ted Conover’s Newjack: Guarding Sing Sing.

Well, did you read any of this? Don’t you agree that this is absolute horror? Don’t you agree that this cries to high heaven, an absolute disgrace, that this whole system is a crime against humanity? If you agree, then can’t we also agree that obsessing about correct speech is a bit frivolous, and that while the availability of unisex loos may be a good thing, it is surely on a different level of importance. What we seem to need here is a sense of proportion. If you do not agree, then maybe you should re-read the part about privatisation and the main article on private prisons in the United States.

It is possible to worry about transgender rights and about the US prison system at the same time, and indeed we should, because they both are connected to intolerance and blindness to the suffering of others. But the fact remains that the second issue affects far more people than the first, and the way in which it affects them is far more serious. That’s why I believe that it is far more important. Imagine the history books about the US in the beginning of the 21st century. What would be more important: “Due to pressure from public opinion, privatisation of federal prisons was reversed, and privately owned prisons are against a US law that was passed in 2019”, or “Separate sex public toilets were outlawed in the US in 2019”. The first sounds great to me, the second, well, to be quite honest, I cannot even imagine this sentence ever to show up in a serious book about US history of the 21st century.

Ask yourself a question. Why are the horrors of the US prison system not on the front page of every serious American newspaper, every single day, until the outrage stops? What does that say about the mainstream news? Well, it says many things. One thing it makes abundantly clear is that the mainstream media only print or broadcast the stuff that their audience is willing to read, hear and see. And that says something about us.

Wikipedia, by the way, for all its flaws and all its white male bias, is an indispensable source of information, because it is not owned by big money. Its founders, Larry Sanger and Jimmy Wales, are heroes. Please get used to the fact that reliable information is priceless, and that it is worth some of your money. Consider making donations to them. They need our support.

Fake news is nothing new. Fake news is what happens if what the public is allowed to hear is determined by public relations agencies and by lobbyists and by newspaper corporations that are worried about readership, rather than by fearless independent reporters concerned about the truth only. Fake news is practically all that the American public gets, and has been getting, for the past few decades.

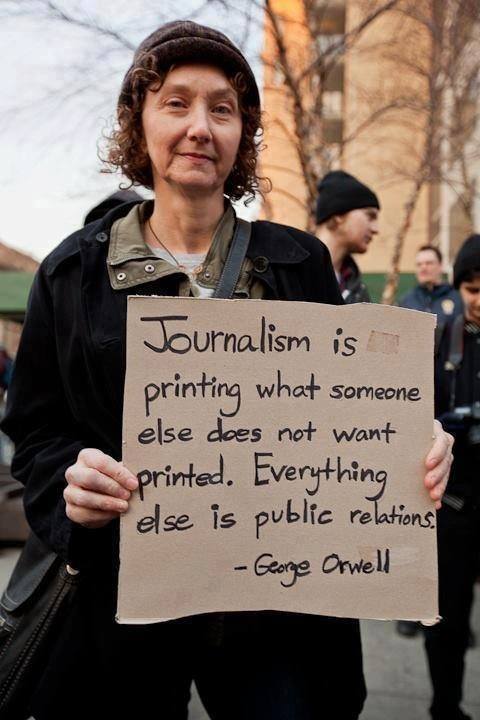

The duty of the serious press, or of serious broadcasting, is to tell the public the truths that it does not want to hear. Fake news is what happens when reporters get addicted to being stars, to being in the limelight, to being adored by their audiences. It is alluring to be a star, but it gives you a position that you do not want to lose. It makes you worry about your job. It makes you vulnerable. And therefore it is at odds with your duty to tell your public unpleasant truths. Doing your duty will make large parts of your public hate you. To quote George Orwell:

Photo from Global Equality

This also holds for intellectuals who get involved in the public debate. We should not shy away from the unconfortable truths. We understand climate change. We also understand the laws of exponential growth, and therefore we should all help sharing the unpleasant truth that economic growth, growth of consumption, is coming to an end. In future, we will all have to consume less, not more. If politicians refuse to say it, scientists should say it and should keep saying it.

A professor of physics that I conversed with about the need for scientists to get involved in the public debate once told me: “Politics is not my thing. Take the discussion about the price of mobility. If you are serious about giving people an incentive to drive less it is obvious what you should do: you should make fuel much more expensive. But politicians do not want to say this, because their voters do not want to hear it. So I have decided to focus on my research instead.”

I can understand, but I do not agree. We need the ceterum censeo (“Furthermore, I think that we all should consume less energy”) of all our physicists, of all our scientists. David MacKay, a Cambridge professor of physics who died in 2016 and who spent several years of his short life educating the general public about the possibilities and impossibilities of sustainable energy, is very eloquent and amusing and worth reading. If you are not yet convinced that energy is a finite resource, and that we will have to change our lifestyles, please consult his website Without The Hot Air and read his book Sustainable Energy, Without the Hot Air. And if you find that you do not want to read such stuff, you might wish to ask yourself why not? Pondering this is good for you, for you are getting closer to asking the eternal question of the philosophers: Which is better, living a comfortable life in ignorance, or living as a true human, making an effort to know the state of the world as it really is?

Energy is a finite resource. Our affluent life style depends on an abundant supply of cheap energy. If we, scientists, or tourists, or both, are flying around the world from conference to conference we are using up the last rays of ancient sunlight. We, researchers, scientists, distinguished professors, will have to give up our frivolous scientific meetings in exotic places. Instead, we should be willing to stay at home, to take a deep breath, and to open our eyes to what is right in front of us. Then, we should start to converse with everyone who is willing to listen, about things that really matter. If we do not want to see this, if we do not want to do this, and if we continue to refuse to act on what we see, we should not be surprised if people, ordinary people, people who have to struggle for a decent living, condemn us all as fakes.